An information hiding technique based on ternary Hamming codes is presented below.

- Introduction

- Ternary Hamming codes

- Efficiency and distortion

- Example using Python

- Message encoding

- A complete Python implementation

- References

Introduction

In the article Binary Hamming Codes in Steganography we have seen how to hide information with binary codes using operations $+1$ and $-1$ on the value of the bytes. However, with binary codes we are only interested in the value of the LSB, so it is not important if the operation we perform is $+1$ or $-1$, which usually leads us to choose it randomly.

Bearing in mind that the operations we perform are of type $\pm 1$ (LSB matching), we could say that we are not taking full advantage of this insertion system. If instead of replacing the least significant bit of each byte, we choose to perform a $\pm 1$ operation, we are working with three possible values: +1, -1 and 0 (we leave the value as it was). So, instead of using a binary code, we can use a ternary code.

The theory behind ternary Hamming codes is the same as that of binary codes. The only difference is that instead of performing operations modulo $2$ we will do them modulo 3. We can get the values $0$, $1$ or $2$.

On the other hand, to hide information in a byte we will need to work with the value of the byte modulo $3$. That is, for a ternary code, a byte with value 233 would correspond to a ternary value $235\pmod 3 = 2$.

Ternary Hamming Codes

Let’s see an embedding example. We are going to use $p=3$, that is, we want to insert a ternary symbol for each modification. To do this, we will work with groups of $ \frac{n^p-1}{n-1} = \frac{3^3-1}{2} = 13$ bytes.

Notice that instead of using $2^p-1$ like in binary codes, we are using $\frac{3^3-1}{2}$. Both cases come from the following formula that allows us to calculate the size of the groups of bytes in which we are going to hide the information:

Suppose that after selecting a group of 13 bytes from the media in which we want to embed the message, and performing the modulo 3 operation, we obtain the following cover vector:

Recall that we also need a matrix that contains in its columns all possible combinations, except the vector of zeros. In this case, in addition, we will have to eliminate the linearly dependent vectors.

One option would be the following:

And finally, we also need the message that we want to hide. Let’s hide for example:

If we calculate the hidden message in our vector $c$ we see that it is:

Logically, it is not the one we want to hide. So we look for which column of M is responsible:

It is column 9 of matrix M. Therefore, to obtain the stego vectpr $s$ we have to add 2 (or subtract 1) to the value of that position in the vector $c$:

It could be the case that, in matrix M, we do not find the column we are looking for, but we do find a linear combination. In this case we would add 1 (or subtract 2).

When the recipient of the message gets the stego vector from the media, they can extract the message by:

Efficiency and distortion

Instead of using $\pm 1$ insertion techniques, we can use $\pm k$ techniques, where $k$ is whatever value we are interested in. However, the larger $k$ is, the more distortion is introduced, so it may not be appropriate to select values that are too large.

If we have used ternary codes for the insertion $\pm 1$, with the insertion $\pm 2$ we will have to use quinary codes, since we have five possible operations: -2, -1, 0, +1 and +2.

In this case the process would be the same as before, changing the value of the module to $n=5$. If we use, for example, $p=3$ we will have to use groups of $\frac{n^p-1}{n-1}=\frac{5^3-1}{4}=31$ bytes.

The same idea would work for other values of $k$ and $n$.

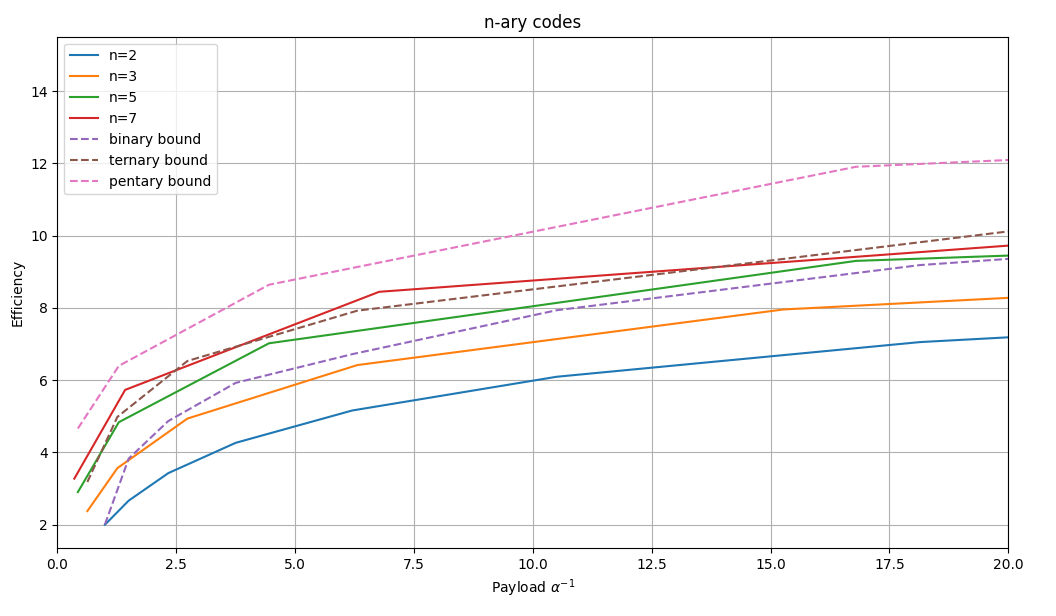

In the following graph you can see a comparison of different n-ary codes. To calculate the payload we will use:

And to calculate the efficiency:

This allows us to draw a graph to see the efficiency with respect to the payload for different values of $p$ and $n$. For better graphical representation, the inverse of payload ($\alpha^{-1}$) is used.

As can be seen in the graph, the higher $n$ is, the greater the efficiency of the method. However, increasing $n$ too much means working with perhaps too large values of $k$, which can greatly distort the media and make the steganographic method more detectable.

However, there is something that cannot be overlooked. The distortion introduced by binary codes is the same as that introduced by ternary codes, since in both cases we only perform $+1$ and $-1$ operations. While in binary codes we choose one or the other randomly, in ternary codes this decision is part of the code. Therefore, the use of ternary codes will offer us more capacity for the same degree of distortion.

In the graph you can also see the theoretical limit for each type of code. As can be seen, these codes do not reach the theoretical capacity.

Example using Python

Let’s look at the Python code that allows us to perform these operations. First we need to prepare the array $M$:

M = np.array([

[1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 2, 1, 2, 1, 1],

[0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 2, 1, 2, 1],

[0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 2, 1, 0, 1, 1, 2]

])

To embed the message $m$ in the vector cover $c$ we only have to find the position of $Mc-m$ in the matrix $M$ and modify it:

import numpy as np

def embed(M, c, m, n):

s = c.copy()

col_to_find = (M.dot(c)-m)%n

position = 0

for v in M.T:

if np.array_equal(v, col_to_find):

s[position] = (s[position] - 1)%n

break

elif np.array_equal((v*2)%n, col_to_find):

s[position] = (s[position] + 1)%n

break

position += 1

return s

To extract the embedded message, just perform the $Ms$ operation:

def extract(M, s, n):

return M.dot(s)%n

Now let’s repeat the example using Python:

m = [2, 0, 2]

c = [0,1,0,0,2,1,2,2,2,0,1,0,2]

s = embed(M, c, m, 3)

new_m = extract(M, s, 3)

>>> new_m

array([2, 0, 2])

Message encoding

Everything seems to indicate that it is more appropriate to use a ternary code than a binary code, since it gives us a higher capacity for the same level of distortion. However, computers represent information in binary, so using a ternary code often requires extra work.

Specifically, we need to be able to go from binary to ternary, and vice versa. This functionality is provided by the function base_repr() of the Numpy library.

Let’s see an example. We will first convert from binary to a decimal number:

>>> binary_string = "1010101011111111101010101010010"

>>> num = int(binary_string, 2)

>>> num

1434441042

Next, we will represent this number in base 3:

>>> ternary_string = np.base_repr(num, base=3)

>>> ternary_string

'10200222011011012000'

To convert back to binary we will do it in a similar way:

>>> num = int(ternary_string, 3)

>>> binary_string = np.base_repr(num, base=2)

>>> binary_string

'1010101011111111101010101010010'

A complete Python implementation

A complete implementation, including encoding and decoding the message, before and after the embedding, is provided in GitHub.

Here is an example where we hide data in an image:

import imageio

cover = imageio.imread("image.png")

message = "Hello World".encode('utf8')

hc = HC3(3)

stego = cover.copy()

stego[:,:,0] = hc.embed(cover[:,:,0], message)

imageio.imsave("stego.png", stego)

stego = imageio.imread("stego.png")

extracted_message = hc.extract(stego[:,:,0])

print("Extracted message:", extracted_message.decode())

References

- Fridrich, J. (2009). Steganography in Digital Media: Principles, Algorithms, and Applications. Cambridge University Press.

There are currently no comments on this article.

Add a Comment